Everything a Symbol

It was the Feast of the Ascension recently in the calendars of both the Western and Eastern branches of the Christian Church. Always on a Thursday and celebrated 40 days after Easter, this is the day on which Christ is described in the New Testament as ascending into heaven before the eyes of his first century followers.

How wonderfully, gloriously strange!

But we live in an age in which the concept of quantum entanglement (in other words, that at the quantum level the behaviour of a particle can have an instantaneous and measurable impact on another at a considerable distance from it—perhaps across billions of light years, astonishingly enough) is not only of theoretical interest but is likely to underpin extraordinary developments in science, particularly in computing and communications (“Beam me up, Scotty” may become possibility, not science fiction!). Einstein’s description of it as “spooky action at a distance” turns out to be not just amusing but accurate: spooky it definitely is. What the “nonlocality” of objects means is that good old spacetime doesn’t seem to hold at a certain level. In fact, the universe really is a lot stranger than most of us have ever imagined, and in this weird world, the notion of Christ’s Ascension begins to look distinctly at home, and cynical materialism not quite the appropriate response to it. Weird, unexpected, strange are very much the right adjectives for both universe and event.

One of Sophia’s poems from the collection Loose Leaves (written when she was 16 after visiting an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts) about the Ascension of Christ comes to mind in contemplating this conjoined oddity. It is also, however, a meditation upon our perception of the numinous. “Everything a symbol,” Sophia says in it. In both art and in religious experience it is meaning that matters. A work of art might be “of” something, a spiritual quest might be “to” something, but it is what it is “about” which has an impact on us.

We are makers and seekers of meaning—and, as Sophia draws to our attention in Loose Leaves, this is a shared journey for all humanity. We moderns must, she said at a reading of poems from Loose Leaves, “keep adding not subtracting meaning, remembering not forgetting.”

In her Ascension poem, woven with words not with an illuminator’s brush of a single squirrel hair, twenty-first century Sophia—lover of both history and science fiction, of both art and the study of religion—rather delightfully fulfils that task, and the meaning of it is a wonderful one.

The moment of Christ’s Ascension is, as Sophia says in the final lines, a “moment of yeast.” Christ’s Last Supper with his disciples took place at the Jewish festival of Passover, which is, of course, the feast of unleavened bread. It marks the fact that the Jewish people had to leave so hurriedly to escape their Egyptian oppressors that they could not wait for bread to rise to take with them. No yeast, therefore, was able to be used. At Passover, Jews celebrate both their freeing from enslavement and the promise made to them by God of the Promised Land. In the symbolic understanding which connects us to the divine mind, Christ is the ultimate Paschal sacrifice, whose death both fulfils ancient prophecy (which is merely symbolic meaning waiting to be understood) and is itself a promise of the Resurrection, the promise offered to all of us, in which the “moment of yeast” for us becomes reality.

Death is our oppressor. Eternal life our Promised Land. Everything is, as Sophia tells us, a symbol. We must just seek to understand.

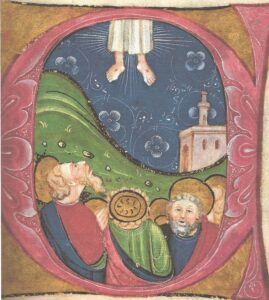

Ascension of Christ, probably Choir Psalter

(Northern Italy, first half of the fifteenth century*)

Literal and flat

The feet rise like those of the hanged man

The drapery hangs like curtains made of paint

Sewn from petals and spiderwebs

And woven with squirrel hair

There can be no blankness here

So the sky is filled with flowers

Woven in pale white vine

The rocks become seams

A peasant patchwork in lieu of a hill

Everything a symbol

Haloes worn like hats

Appearing on the back of the head

Jaunty as a beret

They look up

With their flat faces

Their beards pressed like flowers in a book

Their haloes an estimate of numbers

Let us count now at this moment of the Ascension

Let us count down to takeoff

Those rocket feet

Powered by a wound

One looks out at us

He cannot be identified

He holds nothing in his unseen hands

Maybe it would have been a key

And the man is a rock

Perhaps it is a sword

At this moment of flatness and rising

At this moment of yeast

He turns away from the flames

(*Illumination in the collection of the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia)