Saving Narnia: Sophia, On History

There is a strange and wonderful symmetry to Sophia’s life, as if it was crafted with a writer’s eye; every piece feels necessary and precisely placed, like one of those poignant yet beautiful Russian stories Sophie loved so much, a vivid portrait sketched by Tolstoy.

There is a strange and wonderful symmetry to Sophia’s life, as if it was crafted with a writer’s eye; every piece feels necessary and precisely placed, like one of those poignant yet beautiful Russian stories Sophie loved so much, a vivid portrait sketched by Tolstoy.

One aspect of such symmetry is the deeply embedded nature of Sophia’s love of history. It runs, like a golden thread, through the pattern of her whole life. As I’ve noted elsewhere, living in Italy as a 4-year-old had had a powerful effect on her. At this age too, little Sophia immersed herself in C. S. Lewis’ Narnia stories, the series of which I had read to her.

After Sophie’s death, I reread the Narnia series from beginning to end, seeking to find there an echo of the joy that joyous little child had felt in reading it—and on rereading Prince Caspian, I really understood (in the light of the scholarly yet courageous young woman she had become) why it was Caspian, not any other character, with whom little Sophie had most identified. It made perfect sense. Caspian was, after all, the character who loved “the old stories,” whose favourite subject (taught by his tutor, Dr. Cornelius) was history, who became the champion of the lost but not forgotten (or rather, forgotten not lost) world of Narnia.

The little girl who—toy sword in hand—imagined herself as the brave young prince who fights to protect the beauty of the old world from tyranny and injustice, grew up to be an historian and a writer passionate about preserving the “old stories” in a world every bit as venal and materialistic as that ruled by Caspian’s usurping uncle.

This, however, was to be a battle fought with the pen not the sword—yet it was a battle Sophie thought just as necessary.

Kleio (Clio), the muse of history, daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne (goddess of memory)

Remembering the past is central to the health of any individual or society. To be without memory is to be unanchored from stable identity. Who we are is grounded in everything we have been before; and without that integral sense of continued identity, even though some trace of individual or society may remain, what is left will be incoherent and vulnerable to manipulation or distortion.

Tyrants seek to rewrite history—whether it is a Chinese emperor murdering the scholars of the previous imperial era, or Stalin retrospectively eliminating purged “unpersons” from official records and photographs.

Historians (at least, those who seek to get closer to the truth) are quiet warriors in the service of our remembering ourselves. History isn’t always pretty, and it is never “nice.” It is a complicated business made up of an admixture of the grand arc of movements and empires, and the small detail of individual lives. Nuanced understanding of the past requires interpretation of both micro and macro features, with the final key lying in the historian’s considered (if creatively unfolded) judgement.

In an article Sophie wrote (aged 20) about the historicity of Jesus, she said that most people do not understand the business of doing history. The job of an ancient historian is, she says, like marshalling a legal case based on reasoned consideration of evidence. Logic, not banal empiricism, is the guiding factor in the historical endeavour. History (reflecting its roots in the Greek notion of “historia” or knowledge based on inquiry) necessarily involves exercise of the process of judgement.

Ancient history involves the careful judicial weighing of different sorts of evidence—textual, archaeological, even on occasion scientific—to approach a reconstruction of what might actually have transpired in the past. Like scientific theorists we attempt to save the phenomena by explaining this evidence, but the business of doing it is more like a trial where reasonable doubt is at issue than empirical reasoning. And as in a legal case where innocence is presumed, it is extremely unlikely that an honest historian will be able to tell you that an event certainly never happened or that it is impossible for such-and-such a thing to happen.

From The Historicity of Jesus, Sophia Nugent-Siegal

Sophia herself was fiercely honest. She never fudged her conclusions, or allowed herself to be led by prejudice or ideology. (Sophia made a point, for example, of never reading the introduction to a pre-modern text before reading the text itself. She wanted, first of all, to hear the writer’s voice, and she wanted to hear it unfiltered, unmediated by another’s thought. She always accorded her “witnesses” from the past the dignity of speaking for themselves.) The historian’s job, she believed, was to seek to carefully and deliberatively weigh the evidence in search of the greatest truth available to us—in the service of which the historian must be receptive yet analytical. “Our proper position,” she continues in the same article, “has to be caution, a respectful but critical attitude to our witnesses, both human and artefactual.”

Sophia used to remark, somewhat wryly, that she had often observed that those most stridently calling for “respect for other cultures” in the contemporary setting, seemed to be those least likely to give respect to those who speak to us from that “other country,” the past. Death is a great injustice (Sophia’s too-brief life is painful testimony to that cruel fact), but for the dead to be traduced, manipulated, and misused by the living compounds that injustice even further. Sophia considered that the denizens of history deserve our respect as much as do the citizens of our own era. For her, the people of the past had each a voice—some more significant, more powerful, more insightful than others—but all worthy of being heard. To be an historian, and to be a fair and just one, is thus to be a sensitive listener to those who speak to us across time, allowing them to tell us their stories.

Sophia, age 11, in costume as Henry V, for a recital

Sophia had loved stories all her life. Little Sophie who spent an entire year as a tiny tot pretending to be Prince Caspian, who ran around the playground as a 5-year-old declaiming Henry’s Agincourt speeches from Shakespeare’s Henry V (she’d fallen in love with Olivier’s film of the play, and the entire cycle of the history plays remained amongst her favourites from the Shakespearean canon), who was fascinated as a 5-and 6-year-old by ancient Egypt and hoovered up every source I could find on it, who loved to talk to old people (because they would tell her stories about their lives “in days gone by”), that clever, curious little girl grew up to be the historian to whom thinkers such as Thucydides, Plato, Cicero, Marcus Aurelius, St Athanasius, Dante or the medieval chroniclers spoke with such clarity and directness. She was also the young scholar and writer for whom ancient grave markers (discussed so matter-of-factly in dry academic texts) denoted real mothers, real fathers, real sons and daughters, real human beings present to us even in the face of death—in fact, especially in the face of death, as this remains a profound experience we moderns share with all our ancestors.

History is the human face of the past. It is our story, and Sophia would wish to remind you of just how necessary it is that we keep telling it to ourselves and, more importantly, to our children.

Sophia was, of course, an historian who wrote science fiction. The future, she would tell us, is inevitably made of the past. Whether knowingly or unknowingly, human existence is played out in terms of everything that has gone before. The best futures, however, are those constructed in the full light of knowledge of it.

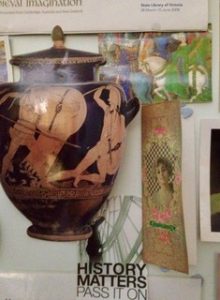

On the wall of photos and images that Sophie collected together, she placed a clipping printed out from the Internet. The injunction, and the play on words, appealed to her. It says this:

HISTORY

MATTERS

PASS IT ON

This is the debt we owe to the future, Sophie’s clear young voice reminds us. History really does matter. We must remember the past. We must tell its stories.

We must save Narnia. It is up to each of us to do it.