Non Fiction

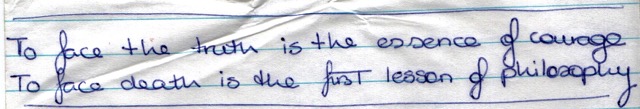

The samples of Sophia’s non-fiction writing provided here cover both formal and informal modes, giving a sense of her cast of mind. It was a worldview Sophia developed early. A speech (given to Rotary), which she wrote when she was 13, reveals that the characteristic tenor of her thought was evident even at that age. When she writes in it of The Winter’s Tale showing her, in its “imperfect happy ending”, the “wise truth” that, like Leontes, we cannot “ …undo all wrongs or heal all sorrows, but must value the joys that we have”, one hears the same clear note of courage, the same philosophic mind with which she was later to face her own mortality. The speech was about truth in literature, but truth was something Sophie lived out in all things. Read “The Truth in Literature” …

The samples of Sophia’s non-fiction writing provided here cover both formal and informal modes, giving a sense of her cast of mind. It was a worldview Sophia developed early. A speech (given to Rotary), which she wrote when she was 13, reveals that the characteristic tenor of her thought was evident even at that age. When she writes in it of The Winter’s Tale showing her, in its “imperfect happy ending”, the “wise truth” that, like Leontes, we cannot “ …undo all wrongs or heal all sorrows, but must value the joys that we have”, one hears the same clear note of courage, the same philosophic mind with which she was later to face her own mortality. The speech was about truth in literature, but truth was something Sophie lived out in all things. Read “The Truth in Literature” …

Essays:

This essay on the Melian Dialogue (which, though academic, is engaging to read) also reflects the continuity of Sophia’s thought, displaying the nuanced interpretive framework she had been developing since childhood. Thucydides was, Sophia said (in a later email to Prof Paul McKechnie), quite her favourite historian, alongside Tacitus. The Melian Dialogue is, of course, the famous moment in history (dramatically represented by Thucydides) in which the Athenians and Melians debate what we would call the “Might is Right” argument. Sophia says of Thucydides that: “Philosophically, what Thucydides is trying to communicate is the inevitably tragic nature of the human condition—no matter which way we turn, whether we do or do not face the truth, we and all our works will eventually be destroyed.” Humanity exists within time, and that tragic awareness necessarily threads through all things. Moreover, Sophia felt that the Dialogue’s dynamic quality not only embodies complexity of theme, but also gives the Dialogue ongoing relevance thousands of years from its creation, so underscoring the importance of the “continuing conversation” between past and future which was so central to her own worldview. Sophia observes that:

“It is the two-sidedness of the Dialogue, in which neither party is granted a privileged position, which has granted it a unique kind of discursive vitality, opening out tragic visions which can be seen alternately from the viewpoint of Dionysius or Bosworth, and the strength of which lies in the continuing conversation, in which the past is necessarily an “aid to the interpretation of the future” and the Histories are thus “a possession for all time” (Th. I.1.23).”

Read – “The Melian Dialogue” …

Articles:

Christian Mission Today: A Young Person’s View was written when Sophia was 19, and was published in St Mark’s Review, No. 217, Aug 2011: 112-115.

The Middle Ages was written by Sophia in the months before she died. She wrote it as an entertainment, for a generalist audience, to keep her busy mind occupied while she was not working on her university studies (which she had had to defer due to the precariousness of her health).

Notes:

Sophia wrote comments on ideas that interested her—things she wanted to think about, ideas she was turning over in her mind. They could be found tucked away in various places—on her laptop, on scraps of paper, or written in notebooks. She was an astute observer, and her comments are of interest in themselves, apart from what they reveal about her thought.

Read – “Society & Politics – from Margaret Thatcher to Game of Thrones” …

Read – “Democracy – Beyond Idealism” …