Sophie’s Eulogy

You will forgive me, I know, if I am not able to give this eulogy without being upset. However, this is a task that only I can do. Soph was the public speaker of our little family, but I know that Sophie would wish me to be the one to speak for her, so I hope you will bear with me, remembering, as Soph would no doubt say to us, that to sorrow is not to despair.

You will forgive me, I know, if I am not able to give this eulogy without being upset. However, this is a task that only I can do. Soph was the public speaker of our little family, but I know that Sophie would wish me to be the one to speak for her, so I hope you will bear with me, remembering, as Soph would no doubt say to us, that to sorrow is not to despair.

In those dark terrible last days in the Intensive Care Unit, a scud of doctors swept into the cubicle where Sophie was lying hooked up to various bits of medical machinery. The chief doctor, whose face I no longer even recall, asked, “And what was the quality of life before?” Someone, a nurse or a more junior doctor replied: ‘She is doing her Masters’, and I, understanding the brutal logic behind his question, added: “She is a poet, and is writing a novel.” The Utilitarian subtext of his question was, of course, quite clear: was this a life worth saving?

The front cover of the booklet for this service answers him.

Sophia Rose Nugent-Siegal 30 July 1991-17 January 2014: A Precious Life.

Sophie was literally unique. As an Internet search will tell you, there has been, and probably only ever will be, one Sophia Rose Nugent-Siegal in all of history. But she was also unique in character and personality. Sophie was a coruscating and dizzying combination of questing intellect, passion, wisdom, honesty, creativity, joyousness, diligence, fierce and sometimes combative determination, and a wonderfully playful wit and humour—and that’s only the abridged version!

I could give you here a list of achievements and prizes that Soph has won over the years: multiple national poetry prizes, essay prizes, debating prizes, art of speech awards, a prize for topping distance education students across the state for year 12 ancient history while still in year 10, early university entry aged 16 attaining results at high distinction level, an undergraduate degree with stellar results, awards such as The Fellowship of Australian Writers Young Poet of the Year and Sunshine Coast Young Australian of the Year for Cultural Achievement, and the publishing of her first book of poetry aged 16. But that data set tells you very little about Soph at all.

Sophie really was a rara avis, a precious and rare little bird, a singular individual . . . and like most singular individuals, her path was never an easy one. The bedrock of her identity was her formidable intelligence, which showed itself from the start. Soph started speaking at 7 months, and from then on sought to be a full participant in any interesting conversation going on! Like most classical heroes, Soph had a portentous birth . . . hazard and difficulty and a final triumph. When she had finally arrived, the midwife whispered into my ear: “ You have a beautiful little girl. She’s just calmly looking around at the world with big eyes. You know, I think this one has been here before.” It was an impression that struck many over her life, this sense of Sophie having an understanding and wisdom beyond her years . . . which is not to say that she was a perfect little Christian saint on trainer wheels. Sophie was a passionate and intense individual, supplied in full measure from both the mercurial poetic Celt and the implacable juristic Jewish sides of her parents’ cultural heritage. But Soph was, from the very start, a seeker after truth. She lived truth, in a way very few of us do. Most of us piece out our daily existence in various shades of equivocation, convincing ourselves it is for the best, but Sophie lived in the world as a clear bright light, unmuddied by hypocrisy or cant. She was just herself. I can truly say, and I mean this literally, that Sophie never lied to me across her entire life, even as a small child. There was fantasy and imagination, but in the things of moment and character, Soph was totally honest with herself and with others (in the eyes of an often hostile world, all too honest). Sophie wasn’t just the most brilliant, she was also the most authentic individual I have ever known. Truth requires courage, and Soph had that in spade loads. With Emily Bronte, she could say with justification, “No coward soul is mine.”

When Kaye and I were planning this service and I was looking at the handwritten poems Sophie wrote in hospital after she was first admitted in July, I came across a note in which she sets out her wishes for her funeral—the readings you hear today are pure Soph: quirky, unconventional, thought provoking. At the top of the page, she quotes Socrates: To face the truth is the essence of courage; to face death is the first lesson of philosophy. Sophie has done both—clear-eyed, realistic, determined. Faced by the cruel disease that took her life, and the trauma and rigours of medical treatment, Sophie never gave in, never lost herself. And her illness gave to her an added sweetness and gentleness, as she came to really value the simple kindness of others that could make difficult situations more bearable. That first admission, when Sophie was arising to consciousness after sedation following a painful bone marrow biopsy, Kaye and I were sitting by her bed. As she struggled to focus her eyes on us, she said,” Oh I am so glad you are here. I love you both.” And that was pure Sophie, without semblance or subterfuge, the plain truth speaking, despite pain and mind-numbing drugs . . . if you were fortunate enough to be loved by her, that love came to you with no caveats. I count myself blessed to have had it.

Sophie was a wonderful daughter to me. She was, as a tiny tot, a truly delightful child—funny, playful, totally engaged with life. Sleep may not have been one of her priorities, but encountering the world was. Every day was an adventure, full of amazing things to see and know. Sophie’s father, Michael, was Jewish, and we gave Sophie a Hebrew, as well as a Christian name: Hepzibah, which means, “My joy is in thee.” This is absolutely true for me. Sophie did bring me joy, every day. She was just such fun to be with—in a way that those who later saw only her intellectual and moral seriousness never appreciated. As a small child her excitement at the world had to have physical expression—sometimes she would literally dance and bounce around the room with ebullience and glee. Nella, the Italian lady at the café where we often used to go for a cappuccino for me and a baby cino for Soph, used to call her, her “bouncing girl”. As a young woman, that playful energy remained an essential part of her character, animating her view of the world. Soph was a seriously funny conversationalist—and I mean the contradiction there. Funny and serious. She looked at things, big and small—from the events of the larger world to those of her own life—with a wicked and subversive sense of humour, in which there was always truth. And Sophie just enjoyed life. She only wanted more of it.

Even in the days of her illness, Soph and I still had fun. The pleasures might have been small—curling up in bed and watching her favourite dvds together, playing a wild game of Scrabble, doing crossword puzzles with her beloved Auntie Kaye, going to the beach and walking or sitting by the sea—Sophie brought to all her experiences such an intensity and awareness, that even these little things had a buzz. Soph never did anything by halves. She gave everything her full attention—whether it was doing a crossword puzzle, writing an academic piece of work, or writing a poem. She was absolutely and totally engaged with it. One of the things that appalled her about the health system that she found herself trapped inside, was the fact that, despite the many wonderful doctors, nurses and staff who did care for and about her, there were within it not only some so-called “caring professionals” who were just plain selfish and unkind (a minority, but a damaging minority), but also those who—despite the fact that people’s lives depended on it, including our dear Soph’s—did not bring to their jobs the kind of diligence and attention to detail that Soph brought to every single aspect of her life. Soph never engaged in self-pity, she never once asked, “why me?’ in relation to her illness. She did not rail against God or the universe or fate. “Why not me”, she said. What did make her angry was the petty meanness, or worse, the unthinking indifference of so many—of too many—small-spirited human beings.

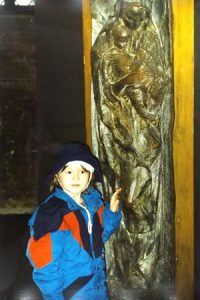

For Soph, there was no distinction between “work” and “play”—there was just being Sophie, and she brought the same passionate intelligence and creativity to every aspect of her life. But there were some things that really did strike her soul. When she was 4, Michael and Sophie and I lived in Italy, in Abano Terme, halfway between Venice and Padua. Sophie had, even before this, showed an interest in the pageant of history. There is a photo somewhere, I haven’t been able to find it yet, of a tiny Sophie, about 18 months old, in a downward-sliding nappy, with a shawl of mine draped dramatically round her shoulders as a cloak, a paper crown I had made for her on her head, wearing the fierce and resolute expression of a medieval monarch. Don’t ask me how she knew it, but this, she had decided, was the stance and mien of a king. When we went to Italy, this incipient attraction to the past became threaded into the very centre of her consciousness. In Italy, art and history are everywhere and Sophie blossomed intellectually within Italy’s environment. It shaped her awareness and her response to the world, and she couldn’t get enough of it. I remember when we went to the Uffizi in Florence, that first time when she was 4, we had to wait for nearly 2 hours in a queue to get in. It was hot, and after a while I said it was all right if she didn’t want to wait, I would understand, but Soph said,” No, I want to stay. I want to see the art.” And so we did. It had a powerful effect. Even as an adult, Soph could recall with absolute clarity that first experience of some of the world’s great works—including being so small that her first perception of Botticelli’s Venus was merely of her feet.

Art was, for Sophie, intimately bound up with religious expression. One of the readings she has chosen for you today concerns Christ and the woman who anointed him with fragrant and costly oil. For Sophie, this is an allegory, on one level at least, of the importance of beauty, of the arts, in our frail human life. Her appreciation of beauty and her innate understanding, even from her early childhood, of human mortality, were bound together. For her, the soaring imperative of the religious quest, and the creative response to the frangibility of human existence, grew from the same place, and it was the place from whence her own poetry came. Her academic and fictional writing involved a great deal more of her own personal intellectual processes, but her poetry was, to use a concept we are uncomfortable with today, genuinely prophetic. It just came to her. She lived it. She breathed it out. It flowed out of her onto the page, as if it was alive.

We live in a small age. We are so used to thinking of ourselves as the apex of civilization, as the pinnacle of human achievement, when in fact, while our technological achievements are great, we are increasingly intellectually and spiritually stunted. Our art is banal, our philosophy tired and obvious, our political theory superficial, our religion empty of ideas. Soph used to say that she was born out of time, and she was right. Her spirit would have found better place in the fierce intellectual battles of the Classical or Medieval worlds, where ideas were worth fighting and dying for. We live in a culture of “nice”, where real intellectual passion is as disconcerting to us as the sight of an uncovered ankle was to a repressed Victorian. Sophie didn’t do “nice”. She did “good”, “moral”, “kind”—but “nice” wasn’t in her vocabulary. It was too small for her large spirit.

For Sophie, everything mattered. Ideas mattered. Art mattered. Religion mattered. History mattered. Philosophy mattered. Life mattered. She was driven by the passion of a deeply questioning mind. Her name—Sophia—which means wisdom in Greek, was not given thoughtlessly. Even when she was an infant, it just seemed right. For it was not just knowledge that Sophie sought across her life—though she loved to learn new things and did so at a phenomenal rate. It was wisdom she was after. Sophie had an instinctive feeling for the human story—whether it took shape in literature, in history, in art, or in the lives of those around her—and the human story is dominated by mortality. Sophie thought that all the great historians were inherently conservative—not in the mean, narrow meaning of our pedestrian age, but in the sense that looking at the sweep of history teaches you one thing: We are born, and we die. Civilizations rise and they fall. There is no inevitable march of progress. There are merely better times and worse times, in which we remain resolutely human, with all our grandeurs and our pettinesses quite intact. Death is our constant, and all the products of our mind and abilities are our answer to it. For Sophie, there was no sense of separation from the flow of history. The voices of the past spoke to her—Plato, Homer, Thucydides, St Athanasius, Dante, Shakespeare—and she listened, and grew wise.

Sophie always thought she would die young. I wished for otherwise. But here we are: my darling girl is dead at 22, with so many of her dreams unfulfilled, so many possibilities yet to be explored. She wanted to finish her Masters, go to Oxford to do a PhD, write an academic text on the role of genealogy in the pattern of European history, write her fantasy series, and then tackle those mature novels based on Medieval history and one on the Emperor Constantine that she was already researching and planning in her mind, but which she wanted to leave till she thought she had the maturity to do them justice. She wanted to be deeply in love, to marry, to have children. She wanted to travel, to participate in the intellectual and political debates of our time. She wanted to live. These things are not to be.

In Shakespeare’s King Lear, when Lear bears Cordelia’s lifeless body on to the stage, Shakespeare gives us one of the most painful scenes in his canon. Lear asks: “Why should a dog, a horse, a rat have life, And thou no breath at all?” It is a good question, and we none of us have an answer. Except in this: Shakespeare quite consciously set Lear in the pagan world of Ancient Britain. Lear achieves personal insight, but without Christian redemption, there can be no movement forward from the bleak worldview of his time. Our Sophie believed in God as a matter of intellectual conviction. You could make a reasonable argument for agnosticism, she said, but atheism was intellectually indefensible. Sophie believed, with Plato and Socrates, in the continuity of the soul, or as Socrates puts it “…the soul, the invisible part which makes its way to a region of the same kind, noble and pure and invisible . . . to the good and wise god whither, god willing, my soul must soon be going.” Moreover, Sophie was a Christian by choice. She believed in salvation and grace—and these were not dull platitudes for her, but matters of conviction. She had given these things a great deal of thought, only heightened over the period of her illness. As her personal selection of readings will make clear, Sophie wanted us to keep in mind what she had learned from her courageous contemplation of her own mortality. Sophie was horrified by the juggernaut of modern medical intervention, but she wasn’t afraid of death. She was convinced that the soul awakens to new life. This is the wisdom she spent her short life achieving, this is the wisdom she would want us to remember.