Fiction

“Novels—an aid to the development of the soul”,

“Novels—an aid to the development of the soul”,

a teenaged Sophia wrote in the margin of one of her notebooks.

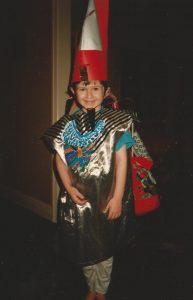

Sophia, in the costume she had made of a Pharaoh, a boy king, wearing Egypt’s double crown, a false beard, and neck collar.

Sophia loved books, she loved stories—she loved reading them, and she loved telling them. She was a born storyteller, always with an edge of both fantasy and history. In a story by a 5-year-old Sophia (who had become fascinated by the Ancient Egyptians), the soul of the Pharaoh’s dead wife comes to him in the shape of a bird to help him defeat an evil enemy with whom he battles in the desert. This rather set the tone for what was to come.

At the time of her death Sophia was working on a series of speculative fiction/sci fi novels set in a universe she created on the basis of a resonant and image-filled dream she had when she was 12 (though she was also doing research for an historical novel she planned next to write on the Plantagenet Stephen and Matilda). In Sophia’s fictional sci fi world, the descendants of humans (some of them genetically-modified for space travel) who crashed on a distant planet called Cicero 5 many centuries into our (old Earth’s) future, have, over subsequent millennia in their historical time, developed a complex world of divergent cultures and civilisations. At this point, however, their world is at a civilisational tipping point, that last moment of old systems before everything changes forever.

For Sophia, as an historian, this was one of the most enthralling and critical areas of study. The arc of time is marked by the ruthless sweeping away of the past at regular intervals. The heartbeat of history is the pattern of the rise and fall of civilisations. As Sophia says in her poem, The Substance of Dreams: “Nature’s dreams are on larger cycles than ours perhaps/ Whole peoples go by while the elements plot merely to reduce the blasphemous graven stone unto godly smoothness”. Shelley’s Ozymandias tells a story of mutability and human hubris that is literally as old as history itself. However, history is also marked by human resilience and continuity—the rulers of the Germanic tribes whose depredations had contributed to the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, for example, came to value Roman civilisation, teaching their children (in a wonderfully ironic twist) the language and values of the people they had conquered.

Sci fi (speculative fiction in general, in fact) offers the opportunity to ask the “big questions”. The issues and concerns that once found their way into epic poetry or drama are now expressed in novels and TV series or movies set in imagined universes. Alexander the Great is said to have slept with a copy of Homer under his pillow; today he would probably have the work of Herbert, George RR Martin, or Tolkien by his bedside.

Sophia’s fictional universe embodies her worldview, a perception of human existence that looked both forwards and backwards in time. It includes genetic modification, clones, ectogenesis, mass drone warfare, AI and mind-machine interface; but it also includes hereditary classes with warfare and government being personally engaged in by the aristocracy, a civilisation concerned with culture and aesthetics (poets, for example, may be poor, but are employed on real world commissions, for issues of social moment), and most of all, despite all the tinkering with the human genome, it remains a distinctly human world.

Sophia was essentially optimistic about the human species. She held a completely realistic view of future history. It wouldn’t always be pretty, it wouldn’t be “nice”, there would be battles and empires and we would repeat everything stupid and vicious, and sometimes everything noble, that we have always done—but it would also be based on relationships, in particular on families, that building block of human society. For good or ill, human interconnectedness—whether love and loyalty or hate and betrayal—remains necessary and powerful in Sophia’s fictional universe, her imagined world beyond our space and time.

The Truth about the Lieutenant is a story Sophia consciously set outside the universe of her other sci fi stories. Sophia wanted to look at the psychological implications of totalitarianism, its subtle but pernicious impact. In The Truth about the Lieutenant, she depicts the totalitarian state not in its bloody extremity, but as a chilly dystopia marked by the suffocating constriction of human feeling. As much poem as narrative, The Truth about the Lieutenant is designed to evoke the estranging distance of dreams…

The Truth about the Lieutenant

by Sophia Nugent-Siegal

Our lives no longer feel ground under them.

At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

Osip Mandelstam

She stood in the centre of the railway station and positioned herself under the skylight, under the perfect blue eye which she could never resolve to think of as sublime or funny, which reminded her of love. She was meant to be listening to the War Minister who was saying something patriotic to the assembled class of graduate secret police. She really did mean to listen to him, she was a loyal servant of the state, but the blue morning kept drawing her eye.

“I am glad to have the chance of seeing you before I receive my orders,” said a voice, unexpectedly near her chair. The Minister must have finished and the audience started to mill around on the stage.

She was embarrassed by the thought he might have noticed her inattention, scared even. She was guilty. She ran her hands across her hips as if they were wet. “Lieutenant,” she said out loud and then whispered, “I couldn’t bear the thought of our separation.” She bit her lip.

Sophia had written 3 complete novels and several short stories within her sci fi universe (in which she had begun writing when she was 16-17). There is a particular poignancy to including here the first chapter of the fourth in the series. Called The Player Kings (reflecting Sophia’s love of Shakespeare), the novel remains unfinished. Sophia wrote a little of it (longhand) each day, even if she was only well enough to do so for 10 minutes, persisting determinedly right up until a couple of days before her death. It mattered a great deal to her to write it, therefore it is only fitting that it is The Player Kings which is featured on her website…

The Player Kings

by Sophia Nugent-Siegal

Chapter One

The sun was high, thin and clear, like a needle of light stabbing at the vain eyes of those who had offended the god of cold. The frost, which had seeped into the fragile bones of the forest’s carpet of skeletal leaves, crackled angrily beneath his mount’s hooves. The trees, upended by the season so that they seemed to be clawing at the sky, at last drew Prince Gaius’ blood, having placed a twig where his cheek would rush past it and be neatly opened. The warmth on his face felt comforting and painless and he desired to lick his lip to taste the iron. It was only the cut which reminded him of his speed.

Leaping over a dead log, he tensed for the final pounce, feeling all the life about him in the deserted winter forest—the cringing things that had fled from the chase, the creature itself in its agony of terror, his brother, riding in from the right, hoping perhaps to steal his glory, and above all some perplexed but predatory seabird a little offcourse. It was exhilarating, sensing these simple things, even with the city and the Palace on the edges of his mind and sight. Gaius had longed—ever since it had become impossible—to live in simple, bright emotions like primary colours. Clearly his feeling was strong enough to flow through the cybernetic interface upon the horse’s withers to impart an extra final jolt of speed.