Flotsam and Jetsam

UK poetry journal, Shearsman, has published another suite of poems (a sequence of eight individual poems), Flotsam and Jetsam, by Sophia in its Spring edition (Shearsman: Vols. 139 & 140). Given the formative years she had spent in England as a child, Sophia would be pleased, both as poet and historian, by the further underlining of this connection.

There is a particular poignancy to Flotsam and Jetsam. Not only does it represent the work with which Sophia signed off on the collection, Rough Sleepers, which had been written through all the difficulty and upheaval of the preceding year, but these were to be the last poems she ever wrote. The sequence was finished, and the collection collated and ordered by Sophia, a few weeks before she died.

The last line of the last poem in Flotsam and Jetsam really was to be the last line.

There are no more—although there were more. As forms the premise of the award in her name (Sophia’s Notebook), on the last day of her conscious life, before the medical procedure which took her life, Sophia asked for a new notebook to be bought for her. She had, she said, “more poems to write.”

I do not know what they were to be. Sophia’s poems always arrived like a flock of exotic birds. One day they were just there: present, whole, alive.

The notebook was bought that day, but Sophia never got to write in it.

However, in the strange way the universe has of organising itself (spun, Sophia might say, on fate’s spindle, woven on its loom), Flotsam and Jetsam stands as a fitting endpoint, both to Rough Sleepers, and to Sophia’s life and work.

So much of her is in it.

Flotsam and Jetsam is highly allusive in its structure. It is simply packed with the rich treasury of Sophia’s mind. History, mythology, philosophy, literature, art, they are all there, and in force (Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “the player prince / Viking amidst his licking dreams” of The Empty Stage, set sail in flaming longboat into death’s dark sea, is a case in point). In fact, the allusive process is itself an allusion, figuring the Classical tradition of referencing the cultural context within which the artist worked. When Sophia was collating the collection a few weeks before she died, she said (with some amusement) that it would take academics decades to decipher all the allusions she had used in Rough Sleepers. (The annotated version would be worth seeing!)

Sophia was a poet in the Metaphysical tradition, a poet of ideas. Flotsam and Jetsam represents a meditation on fundamental existential themes: being / not being; materiality / transcendence. At its core, it is a meditation on death, that “work stoppage perhaps of the breath.” What one sees in her work is, however, not an abstract delineation of an intellectual topic, but an evocation of the thinking mind. There is a pointedly visual quality to each of the individual poems in Flotsam and Jetsam for this reason, an almost dreamlike quality (nightmarish at times) to the imagery, a filmic intensity. No accident, this. It is how the creative mind—whether artistic or scientific—works (linearity is something we impose upon it). Moreover, Sophia was fascinated by film. At one stage in her early teens she had wanted to be a film director. Film (reflecting the significance to her of the visual arts in general) played an important role in her worldview.

Not long ago I watched Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev (Mosfilm has made Tarkovsky’s films available online, they can be viewed here), a film which leaps off (if you watch the film you will recognise the reference) from the life of the great medieval Russian icon painter. The film is structured around eight episodes from Rublev’s life (yes, the numerical synchronicity caught my attention). I have found myself wondering what Tarkovsky would have made of Sophia’s eight poems. He made film with the eye of a poet. In Flotsam and Jetsam, Sophia shapes poetry with a mind-held lens. It would have been a fascinating collaboration.

Sophia would have deeply appreciated Rublev (and Tarkovsky; Soph understood the tragic, yet transcendent, Russian worldview).

The world Tarkovsky depicts in Andrei Rublev is harsh and confronting. All eight episodes are in black and white, the images stark in their clarity. What we see is the reality of the world—the world laid out in all its physicality, folly and cruelty—in which Andrei, a sensitive and spiritual Orthodox monk, must live. The film reaches a crescendo in terrible scenes in a town where betrayal allows a rampaging horde of Tatars to commit every kind of atrocity. Andrei, to protect a woman from being raped, kills the assailant. Horrified, he takes a vow of silence, renouncing his art to perform only mundane tasks in the monastery.

In the last episode, however, Andrei is drawn into the story of Boriska, a young lad who had asserted to soldiers that his dead father had told him the secret of metal-casting (spoiler: he had not). The episode is focussed around the great endeavour of forging a huge church bell, In the end, the boy succeeds. The bell rings out in all its glory—and to the glory of God (the Soviets buried Rublev for a long time: there was, one suspects, not enough Marxist materialism to be found in it).

Boriska, who had fallen to the ground unheedful of water and mud (brute matter in the most literal sense), physically exhausted, emotionally broken, his body wracked with sobbing, is comforted by Andrei who takes him in his arms. Speaking after years of silence, Andrei tells the boy that: “You’ve made a beautiful bell.” And Boriska had. It was a beautiful bell, and it was an achievement made out of imperfection—as all things human must be—beauty reaching beyond base matter to approach “the Real.” The scene ends with Andrei saying to Boriska: “So we will go together. You will cast bells, and I will paint icons.”

The epilogue of the film moves seamlessly to colour, revealing powerful images of Rublev’s haunting icons, these windows through which we see beyond the broken world. Rublev’s art was made out of suffering; not despite it, but because of it, made out of it, as all art which seeks truth must be. Yes, the world is broken, and so are we, but we are also makers—of ideas, of beauty, and of our souls. This is our life’s work, to make “beautiful bells” ringing truly in a muddled world.

It was a principle Sophia herself lived out, by choice and with conviction.

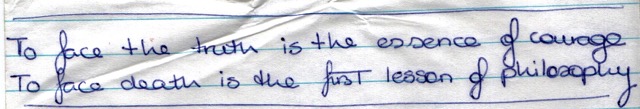

At the top of the notes Sophia had written setting out her wishes in the event of her death (found in her papers days after she died), Sophia had noted, in her clear, firm hand:

And this is what she did. She faced the truth, and she faced death. Flotsam and Jetsam is the final product of the disciplined mind capable of doing so.

If you ask yourself why you should bother reading the work of a very young woman who died all those years ago, here is your answer: because “the wolf will come” and he will come for you. He comes for each of us, and we must have the warrior heart to withstand it.

Sophia, the sweet-faced girl who looks out at us from her photographs, the sweet-faced girl who could confront the thought of her own suffering, her own death, and make art from it, has lessons to teach us.

A long time ago I read that the light from a single candle will continue on, long past our capacity to discern it, to the very edge of the universe.

You made rich and wonderful art, brave-hearted Soph, Tarkovksy’s “beautiful bell” indeed, ringing out on the page.

May the power and beauty of your spirit ripple across time to reach all those who “know to seek” . . .

Flotsam and Jetsam

I—Shipwreck

In the union of the tongue

Coming together and apart are one

The marriage of the sword

Cloven-footed beasts

Like the queen of Sheba

Mistaking a mirror for water

The river begins in the broken word

It becomes Narcissus’ reflection

It becomes Echo’s echo

Her yearning is all voice

Her voice empty of meaning

Like a cracked cup

II—Disguise

Masked in the sea

The spirits rise

Drunk on themselves

To their own selves

Turned in

Like fugitives—or careless coats

The label on the outside

Does not scratch the skin

It is the aureole of Europa

A cloth halo bellied up with salt-wind

Above the hunched back of the bull

The god in meat

Wrapped about the eye

Like a snake

Or a snake-skin washed ashore

A shadow in the sands

III—Quest

We seek to know

But do we know to seek?

In the labyrinth there are no doors

But at its centre Rosamund

What sort of rose is she?

To the philosopher a crystalline sphere

An elemental testament to triangles

To the bishop’s ear a mermaid’s song

Communing each upon the sharpest rocks

But to the fearful and the weak

The rose smells sweet

IV—Recognition

They try the test of mirrors

To see if a creature knows itself

But does a thing ever see itself in mirrors?

Or rather the surface

Like the moon whose craters need telescopes

Stroked by the poets for centuries with goose-quills

And trapped in nets of numbers by the sages

The acrobatics of vision

Bring sight tumbling to the mind

Blocks rolled downhill

It is the patterns written on sand and water which last

What Electra remembered was a curve

And that was how she knew

V—Conspiracy

The suspiration of conspiring breaths

Breeds the spirits between the mouths

The immaterial substances of angel wing and demon foot

Weaving a web like a spider which bites mouths alone

Mandibles clacking out skeins

Like scissors striking aetherial skin

And then Arachne gone

With her Velasquez spinners

Replaced by factories of water and fire

(The new dispensation)

It is from these innards

It is from these inwards parts

Needles that swim like tadpoles through the weft

Combine and strike flame

Devouring the cotton air

And the slave’s hand

Speaking of Caesar

VI—Strike

The cessation and the blow

A work stoppage perhaps of the breath

That is what it all tends to

This gardening of care

This plot to tend

The stem bleeds when cut

A nymph’s torso it might be

Running from a God’s hand

In this stillness

Pointing and growing at the sun

In accusation of life

VII—Rough Music

There is nothing speaks so loud as a wound

The scarlet monarchy of silence deafens

And, like the painter, we wrap ourselves up in our own night terrors

In the shadows we shrink back

Which are really blue

Like bruises

The wolf will come and puff down

The house of shadow

For you could only build it in the light

Such opacity! Daedalus sets jewels

In blind sockets

And makes a living idol

Stone hands are, you see, washed white

VIII—The Empty Stage

At last come to the landing stage

They play dead

Chalk on black

They bathe in flatness

And the flatness must be bathed

The vinegar sponge on Calvary

And the rest is bitterness!

The appeal lost amidst the confusion of tongues

And a burial amidst sweetness!

Borne on the tide the player prince

Viking amidst his licking dreams

And after the last line is cast

Like a lure cast into water

Nothing but ripple and rumour

By Sophia Nugent-Siegal ©

Thank you Robyn. Soph’s poetry is stunning. So great that it has been acknowledged again thanks to you. Your essay on Rublev deserves to be published as well!

Yes, dear Kaye, the poems are stunning.

The combination of power and disciplined restraint (both spiritual and aesthetic) is a potent combination in Soph’s work.

How could that little slip of a thing, so slight, so young, have contained it…but there it is, visible, on the page.