Good Friday—Crucifixion

Easter is the holiest festival in the Christian calendar.

Steeped in compelling reminders of the presence of suffering and of the ineradicable human capacity for evil which all too often ends in such suffering, the story of Easter is one with which modernity, in its relentless “pursuit of happiness,” has become increasingly uncomfortable.

Yet it is Easter that holds Christianity’s deepest truth.

Death, St Paul tells us, is “the last enemy”—and it is death whose final and utter defeat is symbolised in the Easter narrative.

Every year, at Pesach, Jews celebrate not just the freeing of the Jewish people from oppression in Egypt and the survival over millennia of this harried little tribe of exiles, but also the Passover’s re-statement of the covenant made between humanity and God.

For Christians, Easter represents the ultimate fulfilment of that covenant, sealed in the life, death and resurrection of Christ.

There is a poetic wholeness—image wrapped in image, reference in reference—to the Easter story; and there is also a fierce beauty, a symmetry, which poets and artists of the past understood, but to which we are blind.

We have forgotten how to see.

Here in the following poem, written when Sophie was 16, Sophie threads together Jewish and Christian traditions (as those familiar with the Passover Seder will recognise) to remind us to open our minds as well as our eyes—for us to see with the soul the mortal pain we share, the pain for which Christ’s anguish is the transcendent answer.

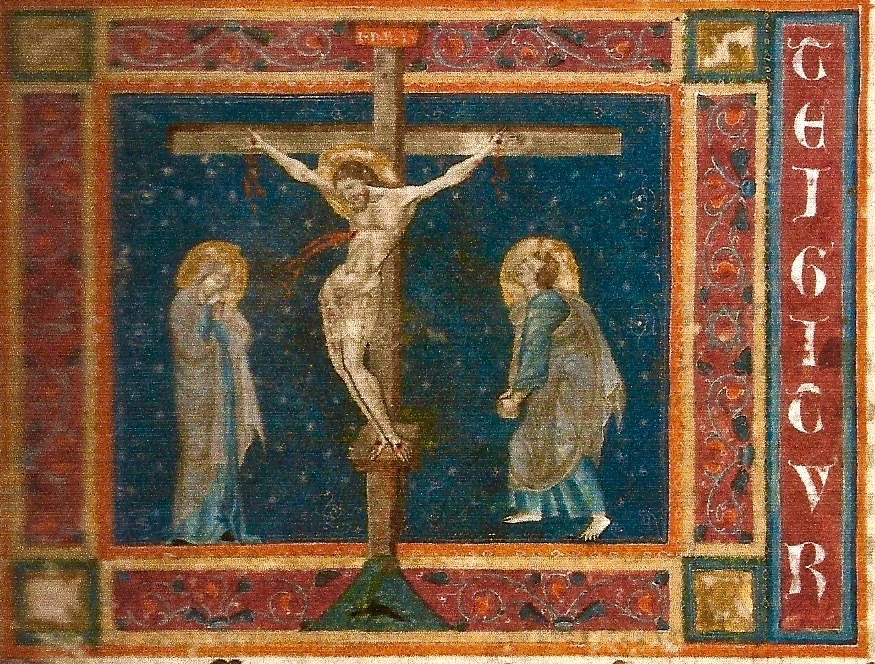

Crucifixion, Missal (Italy, Perugia, before 1297)

The stretched ligaments

Are presented by the suffering eye

The circles of the haloes scuffed by the devotions

Of the monks to the five wounds and the five prayers

The translucent fabric phases in and out of visibility

Thin and pale

Only with the eye an inch away can we make it out

Is this what salvation takes?

This squinting at suffering through a lens

Most of the blood needs a magnifying glass

Only the bright spurt where the lance pierced can be easily made out

The uneven wound that points to his mother

Looking closely a red mark can be found on her gathered-up hand

Is it the stigmata or a splash from overhead?

Heaven-given blood that reminds us of the grace of the Annunciation

And the smudged mandala of the Holy Spirit

The Earth opens up a mouth beyond the frame

Preparing to drink the metaphorical wine

The wine that is used to count plagues and to count blessings

One for the water made blood and one for the nails

One for the frogs and one for the thorny crown

One for the gnats and one for the spear

One for the flies and one for the message over his head

One for sick cattle and one for the crying mother

One for the boils and one for the impassioned saint

One for the thunder and hail and one for the lost thieves

One for the locusts and one for the cast lots

But instead of taking sons God gives one

There will be no pass over for Jesus

For he leans to the left on his cross

John prays for him to save himself

He offers his hand as a stairway and screams at the decorative stars

Mary has suffered and borne for him

And we remember her screams in that stable as she waited for birth

Arms stretched out and meeting nothing

by Sophia Nugent-Siegal ©