A Moment to Look Outside the World…

In the note Sophia left with requests to be undertaken in the case of her death, she asked that a diptych of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection be made and given to St John’s Anglican Cathedral in Brisbane. An extraordinary pair of paintings by Australian artist, Peter Hudson, set in a display case exquisitely handcrafted by traditional craftsman Rob Lamont from Queensland silky oak, has therefore been given to St. John’s in fulfillment of Sophia’s request. (Thank you, dear Peter and Rob, for making her wishes so wonderfully and wholly real, and to the Cathedral for providing a welcoming and embracing space for the Diptych into futurity.)

A diptych of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, what could be more fitting than to speak of it at the season of Easter.

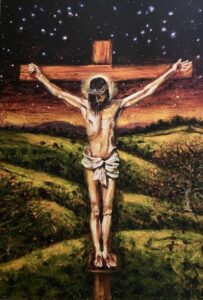

Peter, all of whose work glows with spiritual resonance, has created two powerful images imbued with symbolic meaning. In The Crucifixion, the figure of Christ, stilled in death yet unbroken, arms stretched out to the night sky, stands against a familiar landscape. Sophie was, as Peter says, “a Maleny girl” and the graceful undulations of Maleny’s green hills have themselves become a wild and living element in the work—with Peter’s characteristic thorned, red-blossomed coral trees forming a distinctly apt Queensland reference to the blood of Christ’s Passion.

How beautiful this painting is! In its strength, its symmetry and tonal harmoniousness, in the stillness and endurance figured in the body of Christ, Peter has created a potent and lovely image—an ancient image re-visioned, made new for a new age. Sophia, as an ancient historian who wrote science fiction, would approve and applaud.

Christ’s message is timeless. Beauty is our means of understanding it.

The Crucifixion

© Peter Hudson

In The Resurrection panel of the diptych, once again the lovely Maleny hills form the backdrop against which the moment quietly unfolds. Dawn is breaking, the night withdrawing as the sun’s presence nears. Day is arriving—and in it, heralded by two attendant swallows, those joyful symbols of the soul, a shimmering pillar of cloud (echoing the Old Testament presence of God which accompanied the Ancient Israelites on their journey out of Egypt), its outline brilliant and edged with light, begins to shape itself. If one looks very closely, the merest trace of a human form—head and face—is visible in the circular apex, giving the slightest suggestion of what is to be, the coming moment of transformation. Death is being unmade into life, and the wonder of Christ’s glorious and mysterious Resurrection is about to flower, to unfurl like day itself into full being—into Being.

Glorious and mysterious, because we do not know what happened at Christ’s Resurrection. The New Testament is called a “testament” for a reason. It is the recorded testimony of Christ’s disciples to what they heard and saw—and they did not see the actual moment of transformation. Christ stepped back into the physical world out of their view, invisible to human understanding until he met Mary in the garden and later appeared to the other disciples.

The moment of the Resurrection, this wonderful shimmering moment on the edge of which Peter’s painting is held like a breath, is what we understand beyond simply seeing—which is what art is capable of doing, and what Peter has done, opening up to us possibilities only the soul can know.

The Resurrection

© Peter Hudson

The combination of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection in a diptych is an unusual one—and Sophia, for whom art and art history were a loved and familiar language, chose it quite deliberately. More commonly, the Crucifixion would be paired with a depiction of the Nativity (in fact, representations of the Resurrection itself are rare in the traditions of either the Western or Eastern Churches). However, Sophia—who had had to face, and to conquer, the thought of her own death—is intentionally directing our attention to the “reality of light” of which she wrote in The Substance of Dreams, towards the transcendent truth beyond death.

Nathan Shepherdson, with his poet’s eye for seeing the true, said of Peter’s Resurrection that it depicted “a keyhole for the soul to enter in”—and this is precisely what Sophia would wish it to be, what she intended the diptych to be, an encounter with the Eternal. It is a restatement of her profound trust in God, but it is also a message to us, to all of us who will live into the future in which she would not.

The last lines of the last poem in the collection based on illuminated manuscripts (Loose Leaves) which Sophia wrote as a 16-year-old are a reminder, a guide along the way. In it, she references the artistic process, the creative fact of it, the lovely reality of the illuminated manuscript on which the poem is based, and the mystery and meaning it contains within itself:

Beneath him there is still Earth

Covered with grass and flowers

But it is all made of waves like the sea

Sculpted with a thick brush

All made of circles

The compasses of the cosmos

The fragile and the sacred

The one moment to look outside the world

May it be so for all who come to see the beautiful work Peter Hudson and Rob Lamont have made and which Sophia willed into being.

May it give each of us a wonderful gift: The one moment to look outside the world…

With love, at Easter and always,

R

A keyhole for the soul to enter.

Where Sophie shines still.

True, my friend.

Clear and bright, even beyond death.

Beautiful and true words Robyn. I hope you will send them to the Dean.

Thank you.

Yes, and he has already sent me a lovely image of the diptych this morning!

How wonderful it is!

I am so grateful to the Dean and to Peter and to Rob for making it possible.

Sophie would be so glad…

Well done, Rob. A fine memorial. Life triumphs over death.

All the best,

George

Absolutely, dear George!

As St Paul so forcefully states, there is no victory for death.

It is Love, Sophie would say, which is eternal.